The War Drums Are Stilled: Bears Belly

Indian Scout for Custer Dies

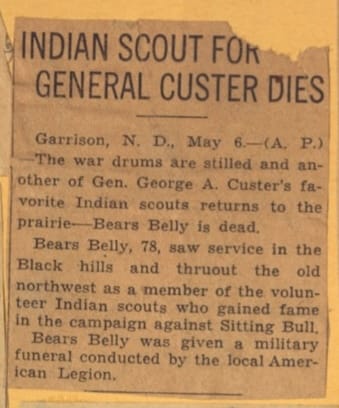

On May 6th, 1933, a short obituary appeared in several newspapers across the country. Written by the Associated Press newswire, the 12-line article told a brief but notable story under the headline: “INDIAN SCOUT FOR GENERAL CUSTER DIES.”

Garrison, N.D., May 6 – (A.P.) The war drums are stilled and another of Gen. George A. Custer’s favorite Indian scouts returns to the prairie—Bears Belly is dead. Bears Belly, 78, saw service in the Black hills and thruout the old northwest as a member of the volunteer Indian scouts who gained fame in the campaign against Sitting Bull. Bears Belly was given a military funeral conducted by the local American Legion.

Behind these few words lay the vast story of a man who lived an adventurous and fulfilling life in a time when two cultures were intersecting and often competing for survival.

Bears Belly's story traversed the prairie lands of the Dakotas, a flat landscape marked with deep crevasses. This creates an image and metaphor for his story, which contains long and deep pathways to explore his life and the beauty of the Arikara people while also surveying the general story of America’s early years and conflicts.

Many people know the story of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and his fateful decision in June of 1876 to rush into battle against the Lakota Sioux, who, unknowingly to Custer, had managed to gather a large force of Indian warriors, including members of tribes who traveled over 750 miles from Missouri, to join the Dakota warriors in their federated fight against the United States and its ever-progressing march across Indian territory.

The results of that battle sent shockwaves across the so-called civilized population of the Americas. Stories of the “Boy General” who died tragically on the prairie at Little Big Horn while leading his Seventh Cavalry to their destruction galvanized a population of adventure lovers who mostly never left their eastern cities. Custer’s death was a devastating event for the U.S. government and for those within European-descended America. George Custer was and still is today an American folk hero.

Most people, however, do not know the story of Bears Belly. This man, an Arikara Indian from the plains and upper Missouri River lands of North Dakota, fought against and alongside the encroaching United States throughout his life.

An Alternative American Folk-Hero Tale

Born into a significantly different world than Lt. Col. Custer’s, Bears Belly’s story interweaves a tale that is thoroughly American and fully Indian.

Bears Belly’s story of his fight for the Arikara is just as important to American history as Custer’s story because it tells the Indian version of the tale that Custer’s life told for the settler side. Both individuals’ lives tell a story of courage and survival in a time when two cultures converged and struggled to understand one another, often failing to do so. The differential power dynamics notwithstanding, both men were thrust into a time and place where they had to make do at all costs to survive. Their lives cannot be relegated to black-and-white stories with little nuance, placing them neatly in “right” or “wrong” categories. Much is lost regarding a historical individual when readers see fit to establish a historical person and story inside a narrow category based on preconceived notions or pre-existing narratives that are fully ensconced in the modern day. Instead, there is much to be learned when readers place themselves in the time and struggles of the historical characters they engage. Fine distinctions and context emerge that give readers insight into the actions and motivations of each subject.

This story doesn’t intend to moralize one individual over another. Yet, there is a straightforward narrative that aligns itself with Bears Belly and Indigenous people from the perspective of the Arikara, looking at the motivations and necessities required of them in the cultural context from which they contended for their survival. I am a direct descendant of Bears Belly on my mother’s side and grew up hearing stories about the man who is my great, great grandfather. My uncle followed Bears Belly’s ways and became a medicine man with his own bear medicine bundle, which he uses in ceremonies, such as my naming ceremony, which is written about in the latter half of this essay.

Bears Belly is an American folk hero just as much as he is an Indian one and is equal to Custer. His life tells the story of the Indian struggle for survival in a time and place where disease, war, and nature constantly challenged that same life within its boundaries. His is just one story in the archives of Indian history, which conveys a wide array of narratives and accounts of Indian life in the days of American settler encroachment. Each of these stories is unique because American Indians are not a monolith any more than American settlers are a monolith. In modern-day America, there are currently 574 federally recognized tribes—sovereign Native Nations—that exist. The Indian population has risen considerably since Bears Belly walked the earth, and Indigenous life as a whole has prospered. But there remain some difficulties as well.

A Fight Not Far Removed From Today

Governmental abuse at the state and federal levels strike at the core of tribal sovereignty—the right to operate as distinct nations within a nation—and poverty and governmental abuse continue to run rampant within tribal governments, mainly run by Indians, along with substance abuse inside reservations and the many urban Indian communities across the country. The struggle for Indian survival continues today; It just looks different. Bears Belly’s fight for Indian identity is still under attack, with many Indigenous people disconnected from their families due to economic reasons or old effects of assimilation policy from the U.S. government, effectively preventing large numbers of American Indians from genuinely connecting with their tribal nations and cultures. However, the majority of Indians are thriving despite these difficulties.

Bears Belly’s story of prospering amid a struggle with a violent usurper is no different, even though it occurred more than a century ago with distinct issues relevant to his time.

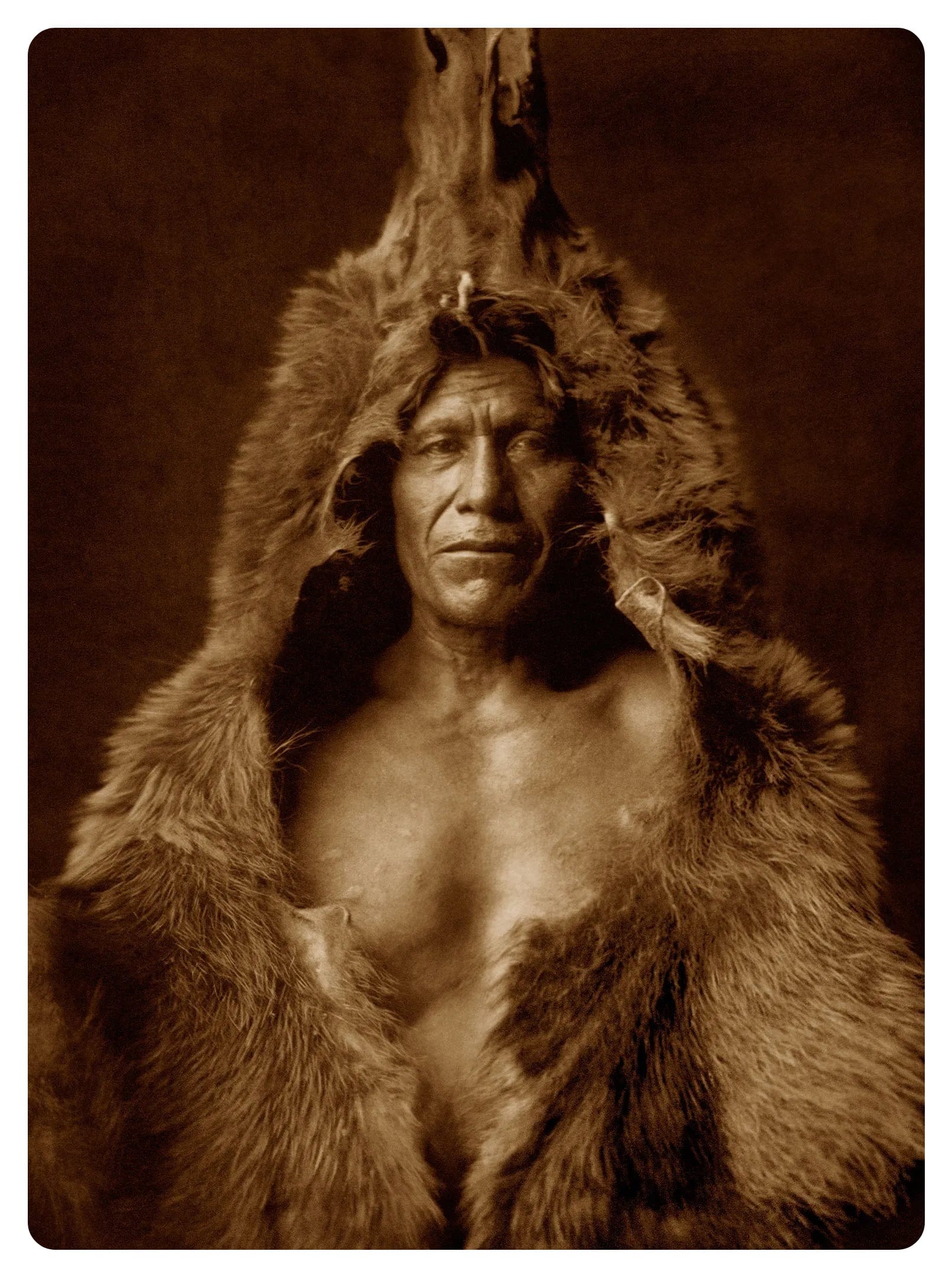

Despite few knowing Bears Belly’s story, many worldwide have seen his iconic photo, taken by the intrepid explorer Edward S. Curtis, which presents Bears Belly’s portrait wearing a grizzly bearskin hide and displaying his scarred bare chest underneath. This photo is often shared online today as an example of vintage cool and rife with American Indian romanticism. In Curtis’ day, the image helped create that same romanticism for many viewers who noted the Noble Savage in his element. The typical stories that came out in the 1700s, 1800s, and early 1900s about the Indians mainly were about savagery and battle. There were noble stories about them, too. Still, Indians were largely feared and seen as inhuman, backward beings, undoubtedly unworthy of the life bestowed upon them due to the horrid tales of how the fierce Indians killed American settlers and even one another cruelly and maliciously.

These same old tales continue to prosper today without knowing the nuance of tribal warfare and interactions at the time, marking the Native peoples of America as an infesting nuisance more than humans to those who take a hardline view against minorities in this country. Custer’s popularity arose from such tales involving his contrasting character of the hero Indian fighter protecting settlers across the West. As a result, Indians were feared and cheered when dead.

Curtis’ photographs and subsequent stories of individual Indians, which he released in 20 volumes over several years, helped to change the public perception of Indians. Now, seeing their pictures and hearing more about their everyday lives, people began to understand the Indian a little more. People began to see the Indian as human, as someone similar to them, and not simply as the bogeyman of the West. Bears Belly’s picture helped start that movement within civilized America toward humanizing and understanding their Indian neighbors.

Through Edward S. Curtis’ photographic lens of a different America and the stories told by the Arikara themselves in those days and chronicled by many other interpreters and writers, Bears Belly’s story is now available for all to immerse themselves in a history that covers historical Native Americans and the human condition, bringing both into the light for readers today to understand America’s Indigenous people a bit more, their struggles and successes, their pains and joys.

Our Unified Story

Ultimately, Bears Belly’s story is our story, that is to say, the story of human life. American Indians are taught a simple principle from very early on: “We are all related.” This concept extends throughout human history and applies to animal life as well. We are all related. We are all one while also uniquely distinct. For an Indian to hate or bring malicious harm to another, including animal relatives, is to violate oneself. So, to understand Bears Belly, one must understand oneself in relation to everyone else.

Over the course of several posts, we will walk together through Bears Belly’s story of survival and fight for Arikara independence. We’ll see triumphs and failures, contradictions and double-dealing, and hope and life. Most of all, we’ll understand the time and people involved in the forming of this nation. And hopefully, we’ll gain a better picture of ourselves in the process.

Bears Belly is an individual, a member of a tribe, and also a symbol of survival and protection for his people. He is a hero, a father, a husband, a medicine man, and a human. To understand Bears Belly better, one must first understand the Arikara and who they are. So, this story begins with life as much as it begins with death.

This is the first of several posts on Bears Belly. A new post on the series will be uploaded each week. Read the second post here.

Member discussion